Organisational Design: Why does Hierarchy persist?

Bioss South Africa with contributions from Robbie Stamp

Bioss South Africa

We live in a globally interconnected VUCA (https://www.bioss.com/blog/becoming-vuca-fit/) world. What are the implications for organisational design?

In recent years, there have been many variations on organisational design, for example ‘flat’ or ‘agile’ organisations, but we still have an understanding of hierarchy as an essential element of organisational design.

On the other hand, we know that today hierarchy is often seen as a dirty word. Because hierarchy is so often seen as being about surbordination. But Bioss sees it differently as a way of enabling good work rather than as a way of getting in the way of good work. We see hierarchies of complexity from the work done at the front line in an organisation directly connecting with customers to the work of a Board of a large global organisation. We also know that in an organisation of a hundred or a thousand, or 10 thousand people, not everyone reports to the CEO. So however flat, holocratic or agile an organisation may be there is inevitably a cascade effect of decision-making, accountability and authorities, even in an organisation that is deeply and appropriately attentive to the perspectives of the people performing different kinds of work at different levels of complexity throughout the organisation.

According to Elliott Jaques (In Praise of Hierarchy, Harvard Business Review, January 1990), the hierarchical organisation “is the only form of organisation that can enable a company to employ large numbers of people and yet preserve unambiguous accountability for the work that they do.”

However, given the human nature of organisations, hierarchy frequently demonstrates its ‘dark side.’ Anyone who has worked in a hierarchically layered organisation can attest to the difficulties that can be created: too many layers, inefficient decision-making, passing the buck, silo mentality, and careerism, to name a few.

Typically when these social problems are created in organisations, our first instinct is to turn to a social intervention: team building, training, coaching, etc. We do not always first ask the question: has the work been structured in such a way that it enables effective performance?

Stratified Systems Theory, developed by Elliott Jaques and built on extensively by Gillian Stamp as Domains of Work (https://www.bioss.com/our-approaches/#levels-of-complexity), observes a universal and naturally-occurring hierarchical pattern in the world of work, based on a difference between the complexity of work at different layers and the time span before the effects of tasks could be seen.

Hierarchy as an enabling factor

When hierarchy is at its most effective, each level of complexity, from the work which people do at the front line through to the C-Suite, has its context set by the next higher level of complexity of work. And arguably, an effective Board recognises the overall context in which the organisation is operating at its widest geopolitical, economic and social level.

The implication of this way of thinking is that the leaders at each increasing level of complexity need to have sufficient capability to provide that context to those working for them.

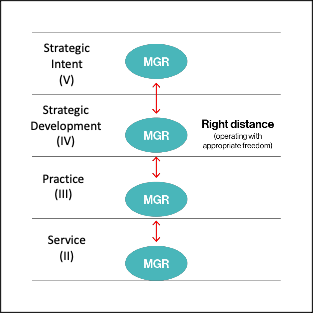

The diagram below illustrates an effective hierarchy of work.

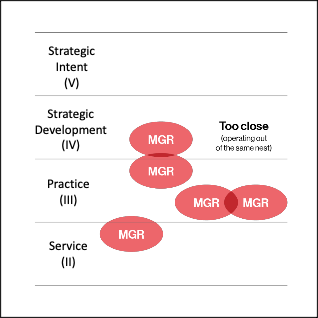

When the leader has the same capability as the subordinates, the potential is created for conflict and a lack of perceived leadership, as in the diagram below.

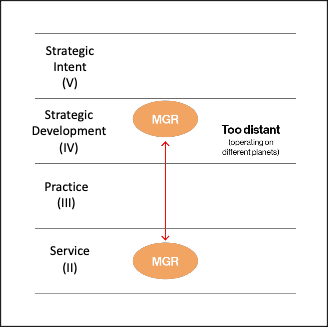

Too great a difference between the manager’s and the subordinate’s work also causes difficulties because the subordinate will not be able to understand the manager’s perspective. In turn, the manager will become impatient with the subordinate’s lack of understanding and inability to ‘keep up’ (see diagram below).

In a hierarchical organisation design, Elliott Jaques sees managerial work as having the following accountabilities:

- Being accountable for the work of their subordinates but ALSO for adding value to their work.

- Sustaining a team of subordinates that are capable of doing the work.

- Setting direction and enabling subordinates to follow willingly and enthusiastically.

The authority in place in order to have the above accountability is as follows:

- The right to veto any applicant who falls below the minimum standards of ability.

- The power to make work assignments.

- The power to appraise performance and, within company limits, make (not recommend) decisions about raises and rewards.

- The authority to initiate removal from the team of anyone who seems incapable of doing the work.

In summary, an effective hierarchy is clear about lines of accountability and the boundaries of discretion in decision-making. In many organisations, though, even those which are considered to be ‘flat’, the required authority in order to maintain that accountability is not present and people end up wondering who makes what decisions where.

Effective hierarchical design ensures that the complexity differences between domains of work are well understood such that leadership can fully assume the requisite accountability for driving performance.

The original version of this post can be found here.

© 2023 BIOSS ™. All Rights Reserved.