Human Potential: The Differential of the Themes of Work Framework

Marcos Luiz Bruno

Managing Director

Instituto Pieron (Bioss Brazil)

When we talk about Human Potential, what comes to mind for you?

We believe that there is a need to clarify concepts, as in practice, terms such as competence, personality types and traits are often mistakenly confused with potential. People talk about potential while most of the time they are actually referring to personality traits, types, styles or skills, and are not considering people’s future growth trends. We need to therefore understand what potential is.

Potential

While living organisms behave as a whole, the usual measurement practices we apply “break” them into parts. This makes it difficult to determine what the organism as a whole is “capable” of – that is, its potential – and this is what causes the confusion.

To start unpacking this, we need to differentiate between “decision-making capability” – what a person is capable of doing – and the person’s specific attributes, personal qualities, or traits. In other words, we need to differentiate between how capable a person is (“how much“complexity they can handle when carrying out their tasks and solving problems) and the way in which they go about accomplishing something (“how” they will behave and interact). When we confuse the “how” with “how much” we lose focus of what we are actually trying to measure. If we confuse the “how” of leadership with the “how much” of potential, we lose sight of the output that we are looking for. In reality, no doubt, we depend on the “how” to the same extent as the “how much”. But it is the latter that makes people uniquely different.

How does decision-making capability differentiate us? Let’s consider a simple analogy. If we were to plant a number of fruit trees of the same species from the same mother tree, in the same soil and under the same environmental conditions, we will still observe marked differences in each tree, be it in terms of size, trunk thickness, the volume of branches and leaves, and the quantity and quality of the fruit. Ontogeny (“the development or course of development especially of an individual organism”) expresses itself differently and seems to have a personal causality. We have no control over it.

As human beings, we are made up of the same parts. However, we see many differences between people. There are obvious differences (such as skin colour, size, gender), but also subtle ones (such as reactions, attitudes, and preferences). All of these differences constitute the “how” of each being.

Something that differentiates every organism is its relationship to time or intentionality. Human capability is uniquely expressed in how far into the future a person can consider consequences when defining objectives, making decisions, and setting plans to transform an intention into results.

This distinctive ability to look ahead and consider something across different time horizons is what we refer to as the “how much”. Some practical examples of different time horizons include: becoming a market leader in the next five to seven years; reducing costs in 15 to 18 months; gaining 25% share in sector X with a given product in up to two or three years; fixing a machine in a week; or developing a management training programme in six months. As individuals, we are intentional beings, guided by goals and able to live with different degrees of uncertainty.

We are equipped with resources to cope with varying degrees of turmoil around us. This is about the “how much”. When we talk about potential, we refer to the “magnitude of the project” that a person can handle over a certain period. Organisations need to know this about their people, as they depend on them to build the future. A future that is not a given, but only considered in the intentions of their leaders, and will be carried out through a process of multiple delegations of responsibilities.

The “how much” is not to be confused with the “how’s”, but is completed by them. People may not be able to complete projects relying on decision-making capability alone. They will need skills such as the ability to engage people and motivate them to demonstrate attitudes like persistence and self-confidence. However, these isolated “how’s” are not enough to enable someone to achieve if they do not have sufficient potential to see complexities ahead, visualise decisions in different contexts and time horizons, or foresee possible alternatives that can be applied in times of turbulence or route deviations.

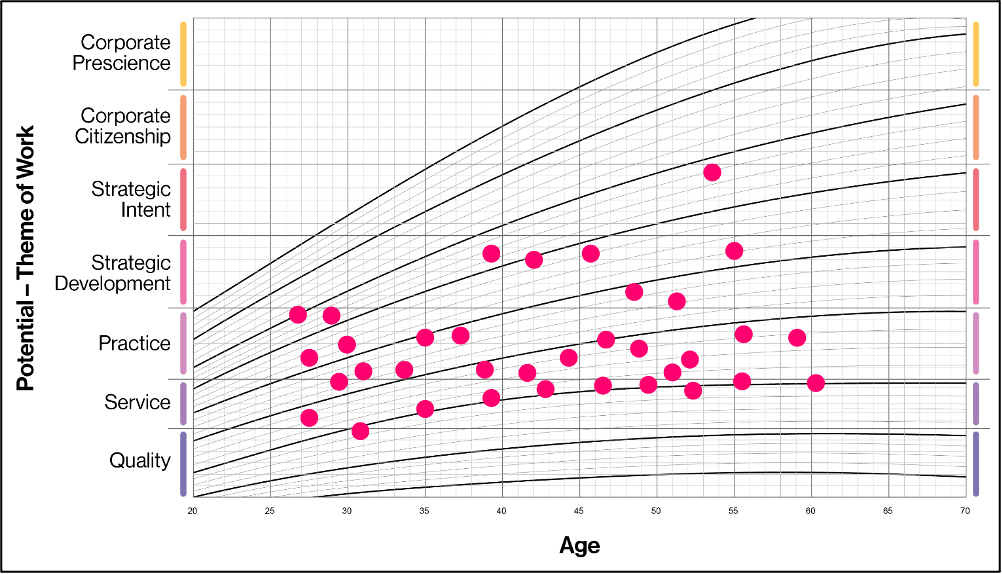

We often fail not because we are “young/inexperienced” or “old/outdated”, but because we cannot see further ahead than others. Youth is not synonymous with greater ability. Old age is not synonymous with stagnation. Our power of judgment grows over time, albeit not at the same speed or to the same levels of complexity as other people. Figure 1 below – Talent Pool – illustrates the relationship between complexity, potential and growth over time.

When we talk about human potential, we are referring to the ability to look to the future and visualise a result, one that has not yet been reached, but which will direct our actions and project the need for resources.

Resources (the “how’s”) are required to realise our potential. These “how’s” can be learned and developed. But it is not the “how’s” that explain what a person is capable of when conditions are uncertain and ambiguous. Our power of judgment in the face of these conditions is what makes the difference. Competencies are allocated resources. But it is not in the competencies where we will find the answer to what human potential is.

Competencies focus on the past, as we are looking at people’s “how’s” across past experiences. However, when we talk about building the future, the differentiator is the ability to look ahead and deal with the ambiguities and uncertainties that will inevitably arise. And new skills will be needed.

Growth in potential

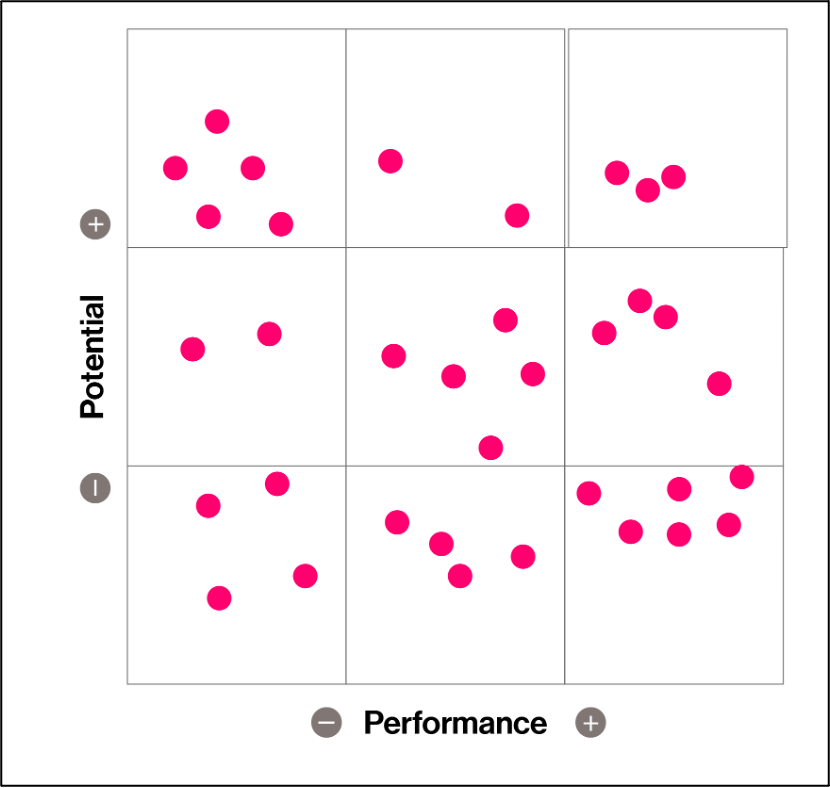

Unfortunately, many organisations still use the BCG Matrix model (originally used in marketing, but renamed the Nine Box Matrix when used by HR) as the basis for analysing their human potential, where people are plotted against Potential x Performance axes (see Figure 2). Quadrants are created, and names or numbers are placed in each quadrant. When one asks what the potential of people in the High Potential x High-Performance quadrant is, the answer is that people can grow into two or three jobs. Now, growing into jobs does not necessarily mean a growth in potential, as different jobs may require the same level of decision-making capability.

The Bioss Matrix of Working Relationships Model clearly illustrates this by defining five themes of work complexity for a complex business unit (and up to seven for some corporations, and indeed, governments). Within each theme, there are many different roles. This allows for career progression and development of the “how’s” without necessarily requiring a change in potential capability. When focusing on decision-making capability, we look at “how much” now, and can also extrapolate to determine how the capability of the person is likely to grow over time, so that we can plan ahead.

The model based on the BCG Matrix (Nine Box) does not provide this information. In reality, it is not based on any theory of human potential. In general, it focuses on the perception of performance based on competencies. But it does not tell us about the “how much” and how this will grow over time.

Thus, it serves to classify people, but does not explain people’s uniqueness, which often leads to biased decisions about people and their performance.

The capability of people in the “low potential” and “high performance” quadrants of the matrix is not taken into consideration using this model, which may be career-limiting.

Further reading: Jaques, Elliott. Social Power and The CEO. USA: Quantum Books. 2002

The original version of this post can be found here.